The transfer of control of the Panama Canal from the United States to Panama was a pivotal moment in modern history, marking the culmination of decades of struggle for sovereignty and self-determination by the people of Panama. The canal, one of the most impressive engineering feats of its time, had been constructed at a cost of over 350 million dollars between 1904 and 1913, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via a waterway through the Isthmus of Panama.

The idea of building a canal across the Isthmus of Panama dates back to the early 19th century, with various countries and companies expressing interest in undertaking such a massive project. However, it was not until the late 1800s that the concept began to gain momentum, driven by the United States’ growing need for a shorter trade route between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

In 1881, the French company Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique de Panama embarked on an ambitious project to build the canal, but it ultimately collapsed due to engineering challenges, financial woes, and tropical diseases afflicting the workforce. The United States eventually acquired the rights to the unfinished canal in 1904 from the French, paving the way for its own construction.

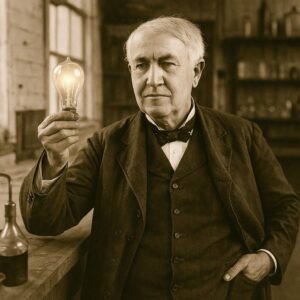

Under the leadership of President Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. embarked on a massive effort to complete the project, with thousands of workers laboring under harsh conditions to excavate and build locks, dams, and other infrastructure necessary for the canal’s operation. The canal officially opened in August 1914, connecting the two oceans for the first time in history.

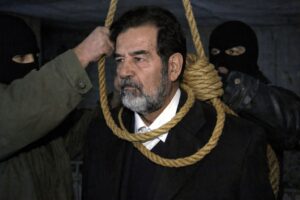

However, from its inception, the United States’ control over the canal was met with resistance from Panamanian nationalists who longed for independence from their colonial past. In 1903, Panama had declared itself an independent republic after a rebellion against Colombia, but it was largely beholden to U.S. influence and control. The U.S.-Panama Canal Treaty of 1977 marked a significant turning point in this struggle, establishing a framework for the gradual transfer of control over the canal from the United States to Panama.

Under the terms of the treaty, responsibility for operating and maintaining the canal would pass to Panama by December 31, 1999. The agreement reflected the shifting balance of power between the two nations, as well as growing international pressure on the U.S. to recognize Panamanian sovereignty over its own territory. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, tensions between the United States and Panama escalated as the deadline for transfer drew near.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government engaged in a high-stakes diplomatic effort to persuade Panama to agree to a range of concessions that would safeguard American interests in the canal’s future operation. This included securing guarantees for the continued use of American military bases along the canal, and negotiating access rights for the U.S. Navy to continue patrolling the waterway.

Despite these efforts, President Mireya Moscoso, who came to power in 1999 following the death of her husband, President Guillermo Endara, refused to grant concessions that would undermine Panama’s sovereignty over its own territory. Her administration worked closely with U.S. officials to ensure a smooth transfer of control on December 31, 1999.

At midnight on New Year’s Eve, 1999, the Panama Canal was officially handed over to the Panamanian authorities in a ceremony at Balboa Heights in Panama City. The event marked the culmination of decades of struggle for independence and self-determination by the people of Panama, as well as a significant milestone in the country’s journey towards full sovereignty.

In the years that followed, Panama invested heavily in modernizing and expanding the canal to meet growing global demand for maritime trade. Today, it is one of the busiest waterways in the world, handling over 14,000 vessels annually. The handover marked not only a transfer of ownership but also a profound shift in the balance of power between two nations.

The significance of this event lies not just in its economic and strategic implications but also in its broader cultural and symbolic importance. For generations, Panamanians had toiled in relative obscurity, working on the canal alongside American engineers and laborers while being denied full rights as citizens. The transfer marked a fundamental shift towards greater recognition of Panamanian identity and culture.

As Panama looked forward to a new era of independence, it also continued to grapple with the legacy of U.S. involvement in its affairs. Many Panamanians remained sensitive about issues of national sovereignty, particularly given ongoing U.S. military presence on their soil.

The transfer of control over the Panama Canal marked an historic milestone in the country’s journey towards full self-determination and international recognition as a sovereign state. It reflected growing demands for justice and equality among Panamanian citizens who had long been subjected to foreign influence and control.

Today, the story of the Panama Canal serves as a powerful reminder of the complexities and challenges that arise when different cultures and nations come together in pursuit of shared goals and ambitions. The legacy of this epic undertaking continues to shape regional politics, international relations, and global trade patterns.

The handover has also sparked new debates about the responsibilities that accompany sovereignty, the role of external powers in shaping domestic policy, and the importance of investing in infrastructure for economic development and growth.

As Panama enters a new era of independence, its people look back on this pivotal moment with pride, knowing that they have forged their own destiny through perseverance and determination. Their story is a testament to the power of nation-building and the enduring spirit of a people who refuse to be defeated by adversity or external interference.

The transfer of control over the Panama Canal was not merely a bureaucratic exercise in transferring ownership; it was a seismic shift in the global balance of power that had far-reaching consequences for both nations involved. The canal, which had been constructed at an estimated cost of $350 million between 1904 and 1913, had long been a contentious issue between the United States and Panama.

The United States’ initial involvement in the construction of the canal was motivated by its desire to establish a strategic trade route that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. The idea of building such a waterway had first been proposed in the early 19th century, but it wasn’t until the late 1800s that the concept began to gain momentum.

The French company Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique de Panama had initially undertaken the ambitious project, but it was plagued by engineering challenges, financial woes, and tropical diseases afflicting the workforce. The United States eventually acquired the rights to the unfinished canal in 1904 from the French, paving the way for its own construction.

Under President Theodore Roosevelt’s leadership, the U.S. embarked on a massive effort to complete the project, with thousands of workers laboring under harsh conditions to excavate and build locks, dams, and other infrastructure necessary for the canal’s operation. The canal officially opened in August 1914, connecting the two oceans for the first time in history.

However, from its inception, the United States’ control over the canal was met with resistance from Panamanian nationalists who longed for independence from their colonial past. In 1903, Panama had declared itself an independent republic after a rebellion against Colombia, but it was largely beholden to U.S. influence and control.

The U.S.-Panama Canal Treaty of 1977 marked a significant turning point in this struggle, establishing a framework for the gradual transfer of control over the canal from the United States to Panama. Under the terms of the treaty, responsibility for operating and maintaining the canal would pass to Panama by December 31, 1999.

The agreement reflected the shifting balance of power between the two nations, as well as growing international pressure on the U.S. to recognize Panamanian sovereignty over its own territory. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, tensions between the United States and Panama escalated as the deadline for transfer drew near.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government engaged in a high-stakes diplomatic effort to persuade Panama to agree to a range of concessions that would safeguard American interests in the canal’s future operation. This included securing guarantees for the continued use of American military bases along the canal, and negotiating access rights for the U.S. Navy to continue patrolling the waterway.

Despite these efforts, President Mireya Moscoso, who came to power in 1999 following the death of her husband, President Guillermo Endara, refused to grant concessions that would undermine Panama’s sovereignty over its own territory. Her administration worked closely with U.S. officials to ensure a smooth transfer of control on December 31, 1999.

At midnight on New Year’s Eve, 1999, the Panama Canal was officially handed over to the Panamanian authorities in a ceremony at Balboa Heights in Panama City. The event marked the culmination of decades of struggle for independence and self-determination by the people of Panama, as well as a significant milestone in the country’s journey towards full sovereignty.

In the years that followed, Panama invested heavily in modernizing and expanding the canal to meet growing global demand for maritime trade. Today, it is one of the busiest waterways in the world, handling over 14,000 vessels annually. The handover marked not only a transfer of ownership but also a profound shift in the balance of power between two nations.

The significance of this event lies not just in its economic and strategic implications but also in its broader cultural and symbolic importance. For generations, Panamanians had toiled in relative obscurity, working on the canal alongside American engineers and laborers while being denied full rights as citizens. The transfer marked a fundamental shift towards greater recognition of Panamanian identity and culture.

As Panama looked forward to a new era of independence, it also continued to grapple with the legacy of U.S. involvement in its affairs. Many Panamanians remained sensitive about issues of national sovereignty, particularly given ongoing U.S. military presence on their soil.

The transfer of control over the Panama Canal marked an historic milestone in the country’s journey towards full self-determination and international recognition as a sovereign state. It reflected growing demands for justice and equality among Panamanian citizens who had long been subjected to foreign influence and control.

Today, the story of the Panama Canal serves as a powerful reminder of the complexities and challenges that arise when different cultures and nations come together in pursuit of shared goals and ambitions. The legacy of this epic undertaking continues to shape regional politics, international relations, and global trade patterns.

The handover has also sparked new debates about the responsibilities that accompany sovereignty, the role of external powers in shaping domestic policy, and the importance of investing in infrastructure for economic development and growth.

As Panama enters a new era of independence, its people look back on this pivotal moment with pride, knowing that they have forged their own destiny through perseverance and determination. Their story is a testament to the power of nation-building and the enduring spirit of a people who refuse to be defeated by adversity or external interference.

The Panama Canal has become an iconic symbol of Panamanian identity and sovereignty, representing the country’s struggle for self-determination and its ultimate triumph over foreign influence. The canal’s history serves as a reminder that true independence requires not only formal recognition but also economic empowerment, cultural preservation, and the ability to shape one’s own destiny.

The handover has had far-reaching consequences beyond Panama’s borders, influencing regional politics and international relations. It marked a significant turning point in the history of Central America, where U.S. interventionism and dominance had long been a reality.

The United States’ involvement in the construction and operation of the canal had created a complex web of interests and allegiances that continued to shape regional dynamics well after the transfer of control. The handover marked a significant shift towards greater recognition of Panamanian sovereignty, but it also underscored the challenges and complexities that arise when nations navigate the intricacies of international relations.

The Panama Canal has become an important case study in international relations, highlighting the importance of diplomacy, negotiation, and compromise in resolving conflicts over territory and resources. The handover serves as a powerful reminder of the need for cooperation and mutual understanding between nations, particularly in regions where historical grievances and unresolved issues continue to simmer beneath the surface.

The transfer of control over the Panama Canal marked not only a new era for Panama but also a profound shift in the global balance of power. As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, the significance of this event is more relevant than ever, serving as a powerful reminder of the importance of cooperation, diplomacy, and mutual respect between nations.

Today, the Panama Canal continues to play a vital role in global trade patterns, with over 14,000 vessels passing through its locks annually. The handover marked not only a transfer of ownership but also a fundamental shift towards greater recognition of Panamanian identity and culture.

As Panama looks back on this pivotal moment, it is clear that the legacy of the Panama Canal continues to shape regional politics, international relations, and global trade patterns. The story of the canal serves as a powerful reminder of the complexities and challenges that arise when different cultures and nations come together in pursuit of shared goals and ambitions.

The transfer of control over the Panama Canal marked an historic milestone in the country’s journey towards full self-determination and international recognition as a sovereign state. It reflected growing demands for justice and equality among Panamanian citizens who had long been subjected to foreign influence and control.

Today, the story of the Panama Canal serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of investing in infrastructure for economic development and growth. The handover has sparked new debates about the responsibilities that accompany sovereignty, the role of external powers in shaping domestic policy, and the need for nations to prioritize their own economic and social needs.

As Panama enters a new era of independence, its people look back on this pivotal moment with pride, knowing that they have forged their own destiny through perseverance and determination. Their story is a testament to the power of nation-building and the enduring spirit of a people who refuse to be defeated by adversity or external interference.

In conclusion, the transfer of control over the Panama Canal marked not only a new era for Panama but also a profound shift in the global balance of power. The handover serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of cooperation, diplomacy, and mutual respect between nations, particularly in regions where historical grievances and unresolved issues continue to simmer beneath the surface.

The story of the Panama Canal is a testament to the complexities and challenges that arise when different cultures and nations come together in pursuit of shared goals and ambitions. It serves as a reminder of the need for nations to prioritize their own economic and social needs, while also working towards greater recognition of sovereignty and self-determination.

As Panama looks back on this pivotal moment, it is clear that its legacy continues to shape regional politics, international relations, and global trade patterns. The story of the canal serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of investing in infrastructure for economic development and growth, while also underscoring the need for nations to prioritize their own sovereignty and self-determination.

The transfer of control over the Panama Canal marked an historic milestone in the country’s journey towards full self-determination and international recognition as a sovereign state. It reflected growing demands for justice and equality among Panamanian citizens who had long been subjected to foreign influence and control.

As Panama enters a new era of independence, its people look back on this pivotal moment with pride, knowing that they have forged their own destiny through perseverance and determination. Their story is a testament to the power of nation-building and the enduring spirit of a people who refuse to be defeated by adversity or external interference.

The Panama Canal has become an iconic symbol of Panamanian identity and sovereignty, representing the country’s struggle for self-determination and its ultimate triumph over foreign influence. The canal’s history serves as a reminder that true independence requires not only formal recognition but also economic empowerment, cultural preservation, and the ability to shape one’s own destiny.

The handover has sparked new debates about the responsibilities that accompany sovereignty, the role of external powers in shaping domestic policy, and the importance of investing in infrastructure for economic development and growth. It serves as a powerful reminder of the complexities and challenges that arise when different cultures and nations come together in pursuit of shared goals and ambitions.

In the years since the handover, Panama has continued to invest heavily in modernizing and expanding the canal to meet growing global demand for maritime trade. The country’s investment in infrastructure has been accompanied by significant economic growth and development, with GDP per capita increasing from $2,300 in 1999 to over $16,000 today.

The transfer of control over the Panama Canal marked a new era of cooperation between nations, as Panama and the United States have continued to work together on various initiatives aimed at strengthening their relationship. The two countries have signed numerous agreements on issues such as trade, security, and environmental protection, reflecting a growing commitment to mutual understanding and respect.

The handover has also sparked renewed interest in the history of the canal and its construction. Museums, historical sites, and other institutions dedicated to preserving the history of the canal have sprouted up across Panama, serving as a reminder of the country’s struggle for self-determination and its ultimate triumph over foreign influence.

Today, the story of the Panama Canal serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of investing in infrastructure for economic development and growth. The handover has sparked new debates about the responsibilities that accompany sovereignty, the role of external powers in shaping domestic policy, and the need for nations to prioritize their own economic and social needs.

The transfer of control over the Panama Canal marked an historic milestone in the country’s journey towards full self-determination and international recognition as a sovereign state. It reflected growing demands for justice and equality among Panamanian citizens who had long been subjected to foreign influence and control.

As Panama enters a new era of independence, its people look back on this pivotal moment with pride, knowing that they have forged their own destiny through perseverance and determination. Their story is a testament to the power of nation-building and the enduring spirit of a people who refuse to be defeated by adversity or external interference.

Related Posts