In the grand theater of American politics, symbols often speak louder than words. They distill ideology, evoke emotion, and crystallize the identity of an entire movement into a single, unforgettable image. Among these enduring emblems, none has stood taller or longer than the Republican elephant — a creature both mighty and gentle, commanding yet dignified, representing strength, perseverance, and resolve. Its rise from the pages of 19th-century satire to the forefront of national consciousness tells not only the story of a political party but also the evolution of American democracy itself.

To understand the elephant’s origin as the symbol of the Republican Party, we must travel back to the uncertain days following the Civil War, when the nation was struggling to heal from its deepest wounds. The Republican Party — barely two decades old — had been forged in the fires of abolitionism and Union preservation. It was the party of Abraham Lincoln, the party that had fought to end slavery and preserve the Union, and now it faced a new test: how to rebuild a fractured nation during the tumultuous years of Reconstruction.

The United States of the 1870s was a place of both hope and hardship. Freedmen were seeking equality, the South was undergoing profound transformation, and the political landscape was as volatile as ever. Within the Republican Party itself, divisions ran deep. Radicals demanded sweeping reforms and federal protection for newly freed African Americans, while moderates sought reconciliation with the South. Meanwhile, the nation’s economy teetered under the weight of debt, corruption scandals, and disillusionment. The Democratic opposition exploited these tensions skillfully, seeking to discredit the Republican establishment that had dominated Washington since Lincoln’s day.

Into this maelstrom stepped Thomas Nast — a German-born illustrator whose pen could sting as sharply as any politician’s rhetoric. Nast, who had fled the turbulence of Europe as a child, brought with him an outsider’s perspective and a passion for justice. By the time he joined Harper’s Weekly, he had already earned fame as a fierce critic of political corruption, most notably through his brutal caricatures of New York’s Tammany Hall boss, William “Boss” Tweed. Nast’s art was not just illustration; it was activism. Through ink and imagination, he shaped the moral consciousness of an entire generation.

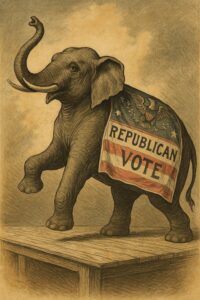

It was in Nast’s satirical genius that the Republican Party found its most enduring icon. On November 7, 1874, Harper’s Weekly published one of his most famous political cartoons, “The Third-Term Panic.” In it, Nast depicted a frightened elephant labeled “The Republican Vote” teetering on the brink of a pit labeled “Chaos.” Around it prowled other political beasts — the Democratic donkey among them — adding to the scene’s sense of confusion and peril. Though the cartoon was not meant to glorify the elephant, the image resonated deeply. To readers across the country, the elephant embodied power, dignity, and reliability — qualities the party desperately needed to project amid growing uncertainty.

Thus was born the Republican elephant. In Nast’s hand, it became more than a creature of satire; it became a symbol of stability in a political era marked by upheaval. The elephant’s massive size suggested might, its intelligence suggested prudence, and its slow, deliberate gait suggested dependability — a counterpoint to the braying donkey that represented the Democrats. It was a stroke of visual genius that would outlive its creator and define a political identity for generations.

Why the elephant? Theories abound. Some historians believe Nast chose it because of the animal’s associations with wisdom and strength in ancient cultures. In India and Africa, elephants had long been revered as symbols of endurance and guardianship. Others point to the animal’s temperament — gentle yet unstoppable when provoked — as a metaphor for the Republican ideal of restrained power. Whatever the reason, Nast’s creation stuck. Almost overnight, the elephant became part of the American political lexicon.

As the decades rolled on, the elephant evolved alongside the party it represented. In the late 19th century, during the Gilded Age, the elephant was often depicted in lavish illustrations that emphasized the prosperity and industrial might of Republican-led America. It appeared on campaign posters, parade floats, and political buttons, always standing firm as a guardian of progress and national unity. For working-class voters, it represented economic opportunity; for business leaders, stability and strength.

By the 1920s, the Republican elephant had become an undisputed fixture of political life. Artists stylized it into a noble, almost heraldic creature, draped in stars and stripes. When World War II erupted, the elephant took on a more patriotic bearing, symbolizing strength and resilience on the home front. In the postwar era, as America emerged as a global superpower, the elephant’s image became synonymous with conservative values — faith, family, free enterprise, and national pride.

But as the Republican Party changed, so too did its elephant. The party of Abraham Lincoln, once synonymous with progress and emancipation, gradually evolved into a coalition of free-market conservatives, suburban voters, and southern populists. Through every shift — the Progressive Era, the Great Depression, the Cold War, and beyond — the elephant remained constant, even as the ideals it stood for were reinterpreted by each generation.

The power of Nast’s creation lies not just in its artistry but in its adaptability. The elephant has been both a rallying banner and a mirror, reflecting the party’s triumphs and contradictions. It has stood for fiscal conservatism under Calvin Coolidge, moral revivalism under Ronald Reagan, and populist nationalism in the modern era. Its endurance speaks to something deeper in the American psyche — the longing for strength tempered by steadiness, tradition balanced with perseverance.

It’s worth noting that Nast’s elephant did not rise alone. His Democratic donkey, born a few years earlier, offered an equally compelling counterpart. The two creatures, locked in perpetual symbolic struggle, came to embody the essence of America’s two-party system. Together they told a visual story of opposition and balance — of competing visions for the same nation. And though Nast himself could never have predicted their longevity, his cartoons gave the United States a political shorthand that remains as potent today as it was in the 19th century.

As mass media evolved, the elephant continued to adapt. By the mid-20th century, it appeared not only in newspapers but also on television, campaign advertisements, and, later, digital platforms. Politicians embraced the iconography with enthusiasm — the elephant featured on podiums, lapel pins, and websites. It came to represent unity within diversity, a reminder that the party’s strength lay in its collective spirit, even when its members disagreed. In this sense, “The Elephant” became more than just a symbol of one party — it became a metaphor for the endurance of American democracy itself.

Today, the Republican elephant stands as a paradox — both an emblem of tradition and a canvas for reinvention. It represents the party’s core ideals of limited government, individual liberty, and national strength, yet its meaning continues to evolve as the country does. Each election season, it reemerges on banners and broadcasts, reminding voters of a lineage that stretches back to the era of Lincoln and Nast. For some, it evokes nostalgia for a simpler political age; for others, it is a call to reclaim the party’s moral compass in a rapidly changing world.

Ultimately, the story of the GOP’s elephant is the story of America itself — a nation forever balancing continuity with change, power with restraint, and vision with realism. Its very survival through wars, depressions, and cultural revolutions speaks to the enduring power of imagery to unite, inspire, and provoke. From Nast’s pen in 1874 to digital memes on the modern campaign trail, the elephant has lumbered through history with unshakable poise, carrying the hopes, contradictions, and ambitions of a party — and a people — upon its back.

In an age of fleeting trends and fractured attention, it is remarkable that one creature — drawn in ink nearly 150 years ago — still commands such recognition. The elephant reminds us that symbols matter, that art can move nations, and that sometimes, the simplest image can capture the deepest truths. Thomas Nast’s creation was more than a political statement; it was a testament to the enduring connection between imagination and identity. The elephant endures because, like the American experiment itself, it is both grounded and grand — a living reminder that strength and wisdom, though heavy burdens, are worth carrying forward.